What is an axiom?

One thing Spinoza does not address in the Ethics is the difference between a definition, axiom, or a proposition (scholia, corollaries, and lemmas I will lazily take to be self-explanatory). This does not mean that he never addresses it. The relevant paragraph is from letter 9 to Simon de Vries (March 1663). In it, Spinoza responds to a query de Vries had made in letter 8 about, “the nature of definition” [IV/38]. Spinoza begins by distinguishing two different kinds of definition. The second kind is a hypothetical, or perhaps to borrow a term that Spinoza used a lot, a feigned definition. This need not be true and in fact may have no referent at all (i.e you can define a pegasus, even though one does not, has not, and never will exist). But a true definition defines the essence of some thing (where ‘thing’ is, as ever, understood as widely as possible; by which I mean a ‘thing’ doesn’t have to be a material object). For instance, Spinoza tells us that love is, “[N]othing but joy with the accompanying idea of an external cause” 3p13s. This is a true definition of the essence of love. But it is not given as a definition because it needs to be demonstrated. Spinoza presumably doesn’t bother telling us that his propositions on the affects are telling us what their essences are (though he does tell us in the Preface to book three that he is telling us what the affects’ “nature and powers” are) because he would have thought that this was so obvious as to be not worth saying. Nevertheless, he does say it, once, in the explanation to the sixth definition of the affects:

Love is a joy, accompanied by the idea of an external cause. Exp.: This definition explains the essence of love clearly enough [emphasis added].

In the letter to de Vries, Spinoza goes on to explain the difference between hypothetical and actual definitions. He asks us to consider two different temples: Solomon’s and one he is imagining. Interestingly, but I don’t believe, importantly, his terminology shifts from ‘definition’ [definitionum] to ‘diagram’ [descriptionem]. When giving a description of Solomon’s temple, Spinoza has to give a “true description of the temple unless [he wants] to talk nonsense”. But when it comes to his hypothetical temple, then then true and false no longer really properly apply. To suggest that somebody’s hypothetical diagram of a temple is false, would be equivalent to saying that they have not conceived what they have conceived. One possibility here that Spinoza does not discuss are impossible objects like chimerae or the goat-stag. Although we may say what a goat-stag is, we actually cannot conceive such a thing. The seventeenth century doctrine of ideas does not allow for ideas of contradictory objects. In this, the doctrine of ideas follows in a long Scholastic tradition that had thought about the relationship between signification and conceptualisation. For a thorough and entertaining overview of the Scholastic debates see Ebbesen’s ‘The Chimera’s Diary’ (Ebbesen 1986). After this discussion of the temples, Spinoza goes on to differentiate definitions from axioms and propositions:

So a definition either explains a thing as it is [NS: in itself] outside the intellect—and then it ought to be true and to differ from a proposition or axiom only in that a definition is concerned solely with the essences of things or of their affections, whereas an axiom or a proposition extends more widely, to eternal truths as well—or else it explains a thing as we conceive it or can conceive it—and then it also differs from an axiom and a proposition in that it need only be conceived, without any further condition, and need not, like an axiom [NS: and a proposition] be conceived as true.

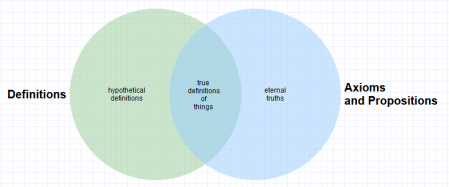

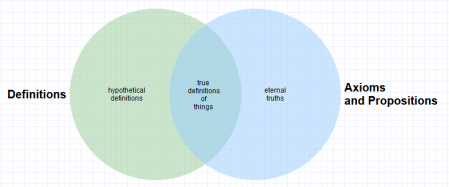

Hopefully the time spent explaining eternal truths for 1d7 now pays off. Definitions explain a “thing as it is”. Axioms and propositions can both do this, but they may also explain ‘eternal truths’; which, if you recall, are necessarily true (for different values of necessarily). Axioms (and presumably propositions) have to be conceived of as true – that’s what being an eternal truth means. Definitions though, can be merely conceived, hypothetically or ‘feignedly’ and in that case do not have to be conceived of as true. If we wanted to be schematic about this, we could have this picture:

So that explains the difference between a definition, a proposition and an axiom. A definition may be true or hypothetically-feignedly false. A proposition must be true, but needs proving. An axiom must also be true, but because of its status as an ‘eternal truth’ does not need to be proved because, “if it is affirmative, will never be able to be negative” (Spinoza 1985b, para. 54, fn. u) [II/20].

The axioms:

I’m splitting my discussion of the axioms as they fall into different levels of difficulty of comprehension (and explanation). So I will not discuss them in the order that Spinoza presents them. First I will discuss axioms 1, 2, 5 & 7 as these are pretty straightforward.

Then I will discuss axiom 3 as this is moderately straightforward in that the content of the axiom is easy enough to understand, but the historical context – as in why Spinoza thought it was an eternal truth and why this a very motivated claim – need some lengthy discussion.

Axioms 4 is not too bad, but again needs some historical background so we can understand just what Spinoza is and is not claiming.

Axiom 6 is a problem. There is a perfectly straightforward interpretation of it – which I will give. I just don’t think that this interpretation is right but don’t want to write an article length discussion on why the standard and straightforward interpretation may not be the best one.

Axioms 1, 2, 5 & 7 (the easy ones)

Axioms one and two reconfigure definitions 3 and 5 – those of substance and mode. They are now eternal truths (I guess we need to throw in some caveat about accepting the law of the excluded middle, but I don’t think anybody before the twentieth century thought that it might be problematic).

Axiom 1

Axiom 1 states that, “Whatever is, is either in itself or in another.” As a definition, this would work for both substance and modes. As an axiom, it is an eternal truth because it is asserting that everything is either ‘A or ~A’ where A=in itself and ~A=in another. We might well wonder what this ‘in’ relation is but Spinoza is relying on us knowing that he is only re-describing the definitions of substance and mode (defs., 3 and 5). Substances are ‘in themselves’; modes are ‘in another’ because a mode has to be a mode of a substance. Everything is either a substance or a mode. Therefore everything is either in itself or in another.

Axiom 2

The same goes for axiom 2, “What cannot be conceived through another, must be conceived through itself.” We are still talking about substance and modes, but now we’re talking about how we conceive substance and its modes. We have shifted from the metaphysical register to the logical one. One interesting thing to note: Spinoza doesn’t simply mimic the structure of the previous axiom. He could have written: “Whatever can be conceived must be conceived through itself or through another”. He doesn’t say this. He starts with a negative: what cannot be conceived through another. This matters as what cannot be conceived through another will turn out to be the attributes of substance. We cannot think extension through anything other than extension. We cannot think thought through anything other than thought.

Axiom 7

Axiom 7 continues the axiomatic approach to substance: “If a thing can be conceived as not existing, its essence does not involve existence.” I suppose the surprising thing about this axiom remains that it appears to be making an axiomatic claim, that is that something is an eternal truth, on the basis of what appears to be flimsy psychological grounds. After all, why can’t I conceive God or substance as not existing? It turns out, that there is a long, complicated and, I will claim, still relevant, set of arguments over whether or not you can actually conceive an impossible, or nonsensical thing. A recent adherent to the claim that you cannot, and I realise that this is a slightly left-field reference, is Daniel Dennett in his article, ‘The Unimagined Preposterousness of Zombies’ (Dennett 1995). His point there is that although you can define a zombie-Spinoza as a creature which is physiologically (down to the last sub-atomic particle) indistinguishable from a human-Spinoza, nonetheless that zombie-Spinoza will lack qualia. There will be nothing it is ‘like’ for that zombie-Spinoza. However, zombie-Spinoza will not know that it is a zombie-Spinoza and will always report that it feels things in just the way it imagines others do. Likewise there is no physical test we can do, because, ex hypothesi, it is physically identical to human-Spinoza. At which point Dennett throws his hands up in despair and says, look: you may imagine that you can conceive of such a thing, but you really can’t. This concept is nonsense; it refers to an impossible thing. Note that there is a suppressed, because mutually-agreed-on-by-both-sides premiss, namely that dualism is false. Descartes thinks that animals are zombies. Descartes can think. Descartes can conceive of zombies because he believes that because two things being physically identical does not rule-out them being immaterially dissimilar. Animals lack the souls that humans have, and so, strictly speaking, feel nothing. Nevertheless we can (in a Cartesian world) imagine a human soul being attached to a cat and then that human-souled-cat would really feel things. That HSC would not be a zombie. To return to (human) Spinoza then: somebody may say that they can conceive of a non-existing substance, or that God does not exist but Spinoza will always insist that despite what they say, they actually cannot. They mis-conceive because they have mis-understood. If somebody understands that God is a being who necessarily exists, then they cannot also conceive a God who does not exist. There are a fascinating few paragraphs on this in the Emendation §§53-54 (where Spinoza has the footnote that defines what an eternal truth is) but discussing them would take me even further afield.

Final point: we can flip this axiom around and I think it is even clearer. Spinoza says, “If a thing can be conceived as not existing, its essence does not involve existence.”

But we could also say: “If a thing’s essence involves existence it must be conceived of as existing.” This is clearly an eternal truth because both clauses are stating the same claim about the relationship between essence and existence; that is: we are merely asserting A = A, though admittedly not obviously so. Spinoza is making the equivalent claim in the axiom. Though admittedly, even less obviously so!

Axiom 5

Things that have nothing in common with one another also cannot be understood through one another, or the concept of the one does not involve the concept of the other 1a5.

I prefer this slightly modified translation:

Things that reciprocally have nothing in common, also cannot be reciprocally understood, or the concept of the one does not involve the other [trans slightly modified]

This is a slightly odd axiom, especially given that I’m lumping it in to the ‘easy to understand group’ of the axioms of book one. Rather than try and explicate it on its own, the easiest approach is just to cheat and see where Spinoza uses it. He only uses it only once in the demonstration to 1p3:

1p3: If things have nothing in common with one another, one of them cannot be the cause of the other.

Dem.: If they have nothing in common with one another, then (by 1a5) they cannot be understood through one another, and so (by 1a4) one cannot be the cause of the other, q.e.d.

What does Spinoza mean by ‘in common’? He tells us this in 1p2:

Two substances having different attributes have nothing in common with one another 1p2.

So what 1p3 is saying is this:

Consider two substances.

Substance-E has the attribute of extension (only).

Substance-T has the attribute of thought (only).

Then substance-E and substance-T have nothing in common (they do not have some third attribute, ‘Henry’ by which they could have something in common).

Then substance-E cannot be the cause of substance-T and vice versa.

How does this help us understand 1a5? As:

1) having something in common means sharing an attribute and

2) attributes are what the intellect perceives as constituting the essence of a substance and

3) “By substance I understand what is in itself and is conceived through itself, that is, that whose concept does not require the concept of another thing, from which it must be formed” 1d3

then

4) attributes also do not need another concept to be understood

5) Which means that when thinking about extension, I do not need thought and vice versa; this is an informal way of saying what Spinoza actually says which is: “the concept of the one does not involve the concept of the other”.

6) But as there is this complete conceptual separation of the attributes, then one cannot be understood through another. How could they, as there is no common concept?

This does kind of feel like I’ve had to demonstrate the truth of axiom 5, but it can be understood on its own so long as already know how strong this idea of ‘nothing in common’ is. Once we realise this is really talking about the attributes and attriubtes are conceptually primary and independent of one another, then axiom 5 does feel like an eternal truth.

OK, so that’s axioms, 1,2 & 5, 7. The easy ones. What about the other three?

Axioms 3, 4 & 6 (the stranger & harder ones)

Axiom 3

From a given determinate cause the effect follows necessarily; and conversely, if there is no determinate cause, it is impossible for an effect to follow.

Surely this is an easy one too? Well, it is easy to understand, yes. What makes it hard, is not the content, but the context. Spinoza is being a little sneaky in making this an axiom. Sneaky may be the wrong word. It’s half sneaky and half overt provacative intervention.

I will explain why.

This axiom is as close to a statement of the principle of ‘sufficient reason’ where reasons, are of course, causes (slightly unnecessary reference to that closet Spinozist Davidson (1963)) as we will find in the Ethics. Is this an eternal truth? After the discovery of radioactive decay and its inherently quantum-mechanical-probabilistic nature … well let’s just say that when Einstein said, “God does not play dice.” This was his most Spinozistic moment; sadly wrong. So today at least we can no longer hold to the principle of sufficient reason or cause as applying universally. But what of the seventeenth century? Well before pushing it back that far, let’s consider an intermediate but well-known figure: Hume:

When we look about us towards external objects, and consider the operation of causes, we are never able, in a single instance, to discover any power or necessary connexion; any quality, which binds the effect to the cause, and renders the one an infallible consequence of the other. We only find, that the one does actually, in fact, follow the other. The impulse of one billiard-ball is attended with motion in the second. This is the whole that appears to the outward senses. The mind feels no sentiment or inward impression from this succession of objects: Consequently, there is not, in any single, particular instance of cause and effect, any thing which can suggest the idea of power or necessary connexion (Hume 2007, VII [6]).

Hume’s critique of the conceptually necessary connection between cause and effect is well-known. It is what legendarily prompted Kant out of his dogmatic slumbers and made him postulate causation (and dependence) as one of the twelve categories of the understanding (grouped under relation with ‘inherence and subsistence’ and community [reciprocity between agent and patient]) (Kant 1999, [A80/B106]). Hume’s claim, following the empiricist line laid down by Locke, is that Ideas are utterly dependent upon impressions (though presumably not causally dependent). If we do not have an impression of something, then unless we can form the idea out of other ideas, then we cannot have that idea and so we do not have knowledge. Do we have an impression of the causal relation? Hume claims we do not. All we see is one ball moving, striking a second and then the second ball moving. What we don’t see is the power, force, impetus, or necessary connection between these two events. Now Hume is not the first to break with the idea that there is a necessary connection between causes and events. He is probably just the most familiar. On the topic of causality, Hume has sometimes been described as a “Malebranche without God”, or “occasionalism without God”. Malebranche (1638-1715 – so born just six years after Spinoza, dies a year before Leibniz does), was an occasionalist. Malebranche certainly knew of Spinoza (see Getchev 1932). There is no evidence that I’m aware of that Spinoza knew of Malebranche. So how could Spinoza have known about occasionalism and why would he need to deny it’s truth in the form of an axiom? Occasionalism is not a doctrine that Malebranche invents. The claim that between cause and effect there is no necessary connection goes back to al-Ghazali and his attack on the Falasafia – the Muslim-Aristotelian philosophers, especially Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna). Here is al-Ghazali in his work, The Incoherence of the Philosophers:

The connection between what is habitually believed to be a cause and what is habitually believed to be an effect is not necessary, according to us […] Their connection is due to the prior decree of God, who creates them side by side, not to its being necessary in itself, incapable of separation. On the contrary, it is within [divine] power to create satiety without eating, to create death without decapitation, to continue life after decapitation, and so on to all connected things (Ghāzālī 2009, 166 [Seventeenth discussion §1]; emphasis added).

and:

As for fire, which is inanimate, it has no action. For what proof is there that it is the agent? They have no proof other than observing the occurrence of the burning at the [juncture of] contact with the fire. Observation, however, [only] shows the occurrence [of burning] at [the time of the contact with the fire] but does not show the occurrence [of burning] by [the fire] and [the fact] that there is no other cause for it (Ghāzālī 2009, 167 [Seventeenth discussion §5]).

Occasionalism, in the figure of Malebranche (1997, 2013) is very much a live possibility in the seventeenth century. Could Spinoza have simply been ignorant of it in all it’s historical forms? This seems exceedingly unlikely. There is scholarly debate over the extent to which Maimonides (whom Spinoza definitely knew well) either knew or engaged with al-Ghāzālī’s work (Stroumsa 2009; cited in Pessin 2016). But perhaps the simplest point to make is this: you don’t bother having an axiom asserting a thing, when that thing is actually completely beyond doubt. If a lack of necessary connection between cause and effect was so unthinkable, then it would have been unnoticeable and so, unsaid. Is there more to be said? does Spinoza ever deal directly with occasionalism? I need to back up a bit here. The short answer is yes he does, but never in a, “So this is why occasionalism is wrong” kind of way. I need to back up and explain a bit about occasionalism, specifically the problem it is sort of a solution to because there is actually a one really important overlap in the philosophical preconceptions between occasionalists and Spinoza.

What’s occasionalism all about when you get right down to it really?

This is actually a simple one to answer: God’s omnipotence. As God is omnipotent, then there isn’t any ‘room’ metaphysically speaking for a finite object to act. It’s all been ‘crowded out’ by God’s own mightiness. There’s an important sense in which, for Aristotelian Western monotheism, one way of thinking about God is as infinite act(ing/ion). It’s also the case that for many occasionalists, from al-Ghāzālī onwards, they also want to preserve the possibility of God intervening miraculously in the world and they recognise that if finite corporeal beings act and act according to necessary physical laws, then miraculous intervention seems to make less sense.

Why do occasionalists from al-Ghāzālī to Hume always start with an epistemic claim? : you don’t actually see causation. There’s a certain simple sense in why epistemology trumps ontology. If I claim that there are no birds and you go – but “Tweetie Pie!” – I’m either going to have to admit that there are birds, or argue as to why Tweetie Pie is not a bird. Al-Ghāzālī and Hume both, first, have to argue that we do not in fact have knowledge of necessary causal relations before they can then claim that there are no such relations.

If we take God’s omnipotence seriously, then it may seem – or at least it did seem – that we only have two options. The first one is occasionalism: what appears to be corporeal actions simply is God moving stuff about. The second one, is Aquinas’s ‘concurrentism’ (see for example, Dvořák 2013). Concurrentism says that we do act, as does God, but at the same time – hence ‘concurrentism’. Spinoza offers a third choice – that may perhaps seem to be more similar to Aquinas than it actually is. The reason why Spinoza can offer a third option is that he denies an implicit presupposition that both occasionalists and concurrentists share: that God is transcendent, in the sense of a transitive cause, and immaterial. Spinoza’s God is an immanent cause. It’s sometimes said that Spinoza reduces everything to God. Bayle’s famous assessment:

Thus, in Spinoza’s system all those who say, “The Germans have killed ten thousand Turks,” speak incorrectly and falsely unless they mean, “God modified into Germans has killed God modified into ten thousand Turks,” (Bayle 1991, 312)

is the epitome of this kind of approach. Spinoza’s point is that the first sentence is not incorrect but that it is strictly equivalent to the second. To the charge that everything is ‘reduced to God’ Spinoza can reply: no, that’s occasionalism. To the idea that his is therefore a theory of concurrentism, he can say: not exactly, it is not the case that God acts concurrently with your action, but that your action and God’s action are the (numerically) one and the same action but understood from different perspectives. Neither occasionalist nor concurrentist, Spinoza’s immanent cause is a new solution to the problem of finite freedom and infinite power.

A note for later: Kristin Primus’s thesis Causal Independence and Divine Support in Spinoza and Leibniz (Primus 2013) deals with this issue. Importantly she argues that the dialogue in Spinoza’s Short Treatise (Spinoza 2002a) is dealing with this very problem.

But really, this needs to be looked at more closely later.

To wrap up this axiom:

We might unreflectively think that an axiom asserting the existence of causal relations would be unproblematic. But whether it’s contemporary discoveries like the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics, or the philosophical tradition of occasionalism, we can’t take this axiom as self-evident.

It only becomes self-evident once a few more pieces of the Spinozist framework are in place: the idea of an immanent cause, the idea that God acts from the necessity of his own nature, the rejection of free-will and the ideas of contingency and possibility, and possibly some other stuff too, but they’re the obvious main ones.

Perhaps the best way to read this axiom is as a deliberate staking out of philosophical territory or an Althusserian-style intervention. Either way it is fighting talk for an eternal truth.

Axiom 4

The knowledge of an effect depends on, and involves [involvit], the knowledge of its cause 1a4.

Effectus cognitio a cognitione causae dependet et eandem involvit

So many decisions are being made and questions ignored in this straightforward translation of 1a4. What kind of cause is Spinoza thinking of? If it is an efficient cause, then translating effectus as effect is perfectly fine. If, on the other hand, the cause is a formal cause, then, although formal causes do have effects, these effects are more like results or conclusions than physical effects. What does Spinoza mean by ‘involves’? Deleuze, for one, will read this as part of Spinoza’s logic of expression: complicating, explicating, implicating. But for the sake of my sanity, I’m going to read ‘involves’ as meaning something less obscure. ‘Implies’ is often what it means. This strengthens the claim that we are not necessarily dealing with a claim about the epistemology of physical systems. Spinoza’s axiom needs to be put in the context of Aristotelian claims about knowledge more broadly. There is a fascinating book, Mancosu’s (1996) Philosophy of mathematics and mathematical practice in the seventeenth century. It starts with a discussion of the historical debate around the status of mathematical proof. How could mathematical demonstration fit within the paradigm of Arisotelian science? This paradigm was built around the syllogism.

We suppose ourselves to possess unqualified scientific knowledge of a thing, as opposed to knowing it in the accidental way in which the sophist knows, when we think that we know the cause on which the fact depends, (10) as the cause of that fact and of no other, and, further, that the fact could not be other than it is […] What I now assert is that at all events we do know by demonstration. By demonstration I mean a syllogism productive of scientific knowledge, a syllogism, that is, the grasp of which is eo ipso such knowledge. Assuming then that my thesis as to the nature of scientific knowing is correct, (20) the premisses of demonstrated knowledge must be true, primary, immediate, better known than and prior to the conclusion, which is further related to them as effect to cause Posterior Analytics I,2 (Aristotle 2001; final emphasis added).

Mancosu goes on to explain:

It is immediately evident that the requirements set down on the premisses-conclusion relation are much stronger than simple logical consequence. In particular, there are several valid forms of inference that do not yield, in Aristotle’s theory, scientific knowledge. In Posterior Analytics 1.13 Aristotle introduced an important distinction between two types of demonstrations—demonstrations tou hoti and tou dioti—which are translated as demonstration ‘of the fact’ and demonstration ‘of the reasoned fact’. In the later Latin commentaries they were often called demonstratio quia and demonstratio propter quid. The former proceeds from effects to their causes, whereas the latter explains effects through their causes. Aristotle gives the following examples. Suppose one wants to prove that the planets are near the earth. One could argue as follows:

The planets do not twinkle.

What does not twinkle is near the earth.

Therefore, the planets are near the earth.

This demonstration, says Aristotle, is a demonstration of the fact but not of the reasoned fact. Indeed, he explains, the planets are not near the earth because they do not twinkle, but they do not twinkle because they are near the earth. In this case we can reverse the major and the middle of the proof so as to obtain a proof of the reasoned fact.

What is near the earth does not twinkle.

The planets are near the earth.

Therefore the planets do not twinkle.

The second type of syllogism is superior to the first, according to Aristotle, because in it an affection (not twinkling) is predicated of a subject (the planets) through a middle term (being near the earth) which is the proximate cause of the effect (Mancosu 1996, 11).

Are we definitely in the realm of the Aristotelian syllogism? No, not definitely. Ascribing Aristotelianism to Spinoza is always tricky. But I think it makes sense to read Spinoza, if not explicitly appealing to a syllogistic account of scientific explanation (that would be taking things too far), then at least being in the ballpark where to understand an effect-result means understanding the implicative reasons stemming from the cause of that effect-result.

Axiom 6

A true idea must agree with its object [ideato]

Fair warning: I think I am about the only person who doesn’t think that this is a straightforward definition of a correspondance theory of truth. It does, I admit, look like a correspondance theory of truth, but a big part of that comes from translating ‘ideato’ as ‘object’ and ‘convenire’ as ‘agree’. Again, full disclosure: everybody (in the English translation) does and only Shirley flags that there might be something odd about this by leaving ‘ideatum’ in the Latin:

A true idea must agree with that of which it is the idea (ideatum) (Spinoza 2002b, 218).

Idea vera debet cum suo ideato convenire [II/47].

I don’t have a fully worked out replacement for this axiom giving us a correspondance theory of truth; nor do I have an absolute knock-down argument as to why it is not. I’m going to restrict this discussion to a list of points for consideration:

-

This isn’t a definition of truth. It is an axiom telling us what a true idea must do.

-

‘ideatum’ is an odd bit of scholastic terminology and mostly means the product of another (divine) idea – we could translate it as ideation

-

‘convenire’ again has a technical history in scholastic philosophy, Heereboord and Burgersdijk use it in a logical context to mean ‘the same’ or ‘identity’

-

what makes this really tricky is how this axiom interacts with other moments in the Ethics, especially the definition of adequate idea in 2d4

-

and that raises a whole new set of questions – especially about the difference, or not, between ‘objectum’ and ‘ideatum’

-

1a6 is used in the following six places: 1p5dem, 1p30dem, 2p29dem, 2p32dem, 2p44dem, 2p44c2dem

-

we can’t truly understand what Spinoza means in this axiom without looking at those six uses, and that would take me too far afield

So I’m going to leave this axiom there. It may be a statement of a correspondance theory of truth, but if it is, it’s an odd one.

Bibliography

Aquinas, Thomas. 1998. ‘Disputed Question on Truth, 1’. In Thomas Aquinas: Selected Writings, edited and translated by Ralph McInerny. London; New York: Penguin Books. https://www.overdrive.com/search?q=39FD7D27-A542-4EAD-A41B-FADCDBE199DD.

Aristotle. 2001. The Basic Works of Aristotle. Translated by Richard McKeon. The Modern Library Classics. New York: Modern Library.

Bayle, Pierre. 1991. Historical and Critical Dictionary: Selections. Translated by Richard H. Popkin. Hackett Publishing.

Burgersdijk, Franco Petri. 1640. Institutionum metaphysicarum. Amsterdam: apud Hieronymum de Vogel.

———. 1701. An Introduction to the Art of Logick. Translated by Anon. London: T. Ballard, at the Rising Sun in Little Britain.

Davidson, Donald. 1963. ‘Actions, Reasons, and Causes’. The Journal of Philosophy 60 (23): 685–700.

Dennett, Daniel C. 1995. ‘The Unimagined Preposterousness of Zombies’. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2 (4): 322–26.

Dvořák, Petr. 2013. ‘The Concurrentism of Thomas Aquinas: Divine Causation and Human Freedom’. Philosophia 41 (3): 617–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-013-9483-9.

Ebbesen, Sten. 1986. ‘The Chimera’s Diary’. In The Logic of Being: Historical Studies, edited by Simo Knuuttila and Jaakko Hintikka, 115–43. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Getchev, George S. 1932. ‘Some of Malebranche’s Reactions to Spinoza as Revealed in His Correspondence with Dourtous de Mairan’. The Philosophical Review 41 (4): 385–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2179800.

Ghāzālī, Abū-Ḥāmid Muḥammad Ibn-Muḥammad al-. 2009. The incoherence of the philosophers =: Tahāfut al-falāsifa. Translated by Michael E. Marmura. 2. ed. Islamic translation series. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young Univ. Press.

Hübner, Karolina. 2015. ‘On the Significance of Formal Causes in Spinoza’s Metaphysics’. Archiv Für Geschichte Der Philosophie 97 (2): 196–233. https://doi.org/10.1515/agph-2015-0008.

Hume, David. 2007. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. Edited by P. J. R. Millican. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kant, Immanuel. 1999. Critique of Pure Reason. Edited and translated by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Macherey, Pierre. 2001. La premières partie, la nature des choses. Vol. I. V vols. Introduction à l’éthique de Spinoza. Presses Universitaires de France – PUF.

Malebranche, Nicolas. 1997. Elucidations of the Search After Truth. Edited and translated by Thomas M. Lennon and Paul J. Olscamp. Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2013. Dialogues on Metaphysics and on Religion. Translated by Morris Ginsberg. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

Mancosu, Paolo. 1996. Philosophy of Mathematics and Mathematical Practice in the Seventeenth Century. New York ; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parkinson, George Henry Radcliffe. 1977. ‘“Truth Is Its Own Standard”: Aspects of Spinoza’s Theory of Truth’. Southwestern Journal of Philosophy 8 (3): 35–55.

Pessin, Sarah. 2016. ‘The Influence of Islamic Thought on Maimonides’. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Spring 2016. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/maimonides-islamic/.

Primus, Kristin. 2013. ‘Causal Independence and Divine Support in Spinoza and Leibniz’. http://dataspace.princeton.edu/jspui/handle/88435/dsp01h415p966c.

Robinson, Lewis. 1928. Kommentar zu Spinozas Ethik. Leipzig: F. Meiner.

Sangiacomo, Andrea. 2016. ‘Aristotle, Heereboord, and the Polemical Target of Spinoza’s Critique of Final Causes’. Journal of the History of Philosophy 54 (3): 395–420. https://doi.org/10.1353/hph.2016.0061.

Spinoza, Benedictus de. 1985a. The Collected Works of Spinoza, Volume I. Translated by Edwin M. Curley. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

———. 1985b. ‘Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect’. In The Collected Works of Spinoza, translated by Edwin M. Curley, I:7–45. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

———. 2002a. ‘Short Treatise on God, Man, and His Well-Being’. In Spinoza: Complete Works, edited by Michael L. Morgan, translated by Samuel Shirley, 31–107. Cambridge: Hackett.

———. 2002b. Spinoza: Complete Works. Edited by Michael L. Morgan. Translated by Samuel Shirley. Cambridge: Hackett.

———. 2016. The Collected Works of Spinoza, Volume II. Translated by Edwin M. Curley. Vol. 2. 2 vols. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stroumsa, Sarah. 2009. Maimonides in His World Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker. Jews, Christians, and Muslims from the Ancient to the Modern World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Notes

“Il faut surtout noter que cet énoncé, ainsi compris, n’est pas une définition de la vérité” (Macherey 2001, I:60).

“It is important to note that this statement, thus understood, is not a definition of the truth.”